This story will meander in the fashion of the river that

provides its background, but it begins with a tableau. Wichita-based poet

Albert Goldbarth stands overlooking a waist-high plinth and beyond—to the

Arkansas (accent on the second syllable) River toward what used to be New Spain

but is now South Wichita. It’s raining on Albert and the plinth and the rest of

us. He’s standing under one of those MOMA catalog umbrellas, the one with the

image of fluffy white clouds and blue sky on the underside so that he's always

in fair weather. As must be the case for anything to be interesting, incoming

information here is complex and contradictory. The words cast on the

rain-spattered plinth are Albert's.

Trichloroethene (a.k.a. Tricky) was first produced in the 1920s and used as an invaluable field hospital anesthetic during World War II—invaluable because it didn't seem to attack a patient's liver as chloroform does or tend to blow up like ether. However, as is the case with a lot of things that look good during wars but later on turn out otherwise (DDT is a great example), Tricky revealed its nasty self to be toxic and carcinogenic; its use in the food and pharmaceutical industries has been banned in much of the world since the 1970s. Tricky has persevered, however, as a heavy-duty degreaser.

In 1991, Trichloroethene—along with a carcinogenic and toxic posse including

Tetrachloroethene (dry-cleaning fluid), 1,2-Dichloroethene, and good old vinyl chloride—was found in the groundwater in a 5 ½ square mile area under downtown Wichita, a few blocks north of the Goldbarth/umbrella/Arkansas River scene. Immediately everyone did what good civic and business leaders do—they hastened to assign blame, threaten litigation, and figure out how to avoid a cash hemorrhage. Eventually the federal government intervened with the threat of a Superfund site and its attendant baggage, and out of desperation—and ten years after the contamination was discovered—Wichita created WATER, the Wichita Area Treatment, Education & Remediation Center, which sounds more like a substance abuse treatment hospital. And of course, in a way, it is.

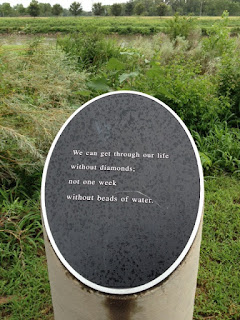

Contaminated groundwater is gathered through extraction wells and miles of piping, treated and remediated at the WATER site, and released into the Arkansas. The vision for the treatment facility included the city park where it was located and the notion of a social and educational public place. Realizing that a world-class poet lived in town, planners advanced the idea of a rather implausible wedding of poetry and hydrology. As a happy result, paths meander through park landscaping and lead walkers past other plinths, each displaying four Goldbarth lines, expressions of the pervasive interconnection of humans and their environment. On one, the trees remind readers "Like you, we're silos of water," on another, "The life of water never ends / it merely has different bodies." Here’s a third:

In a second set piece, Goldbarth is standing before one of

three observation windows that are built into a wall of the treatment facility

and that provide a cloudy view of an aquarium featuring native Kansas fish.

Next to the reflection of the poet’s head, a good-sized sunfish floats

motionless. Above the window is more Goldbarth language, the first line of a

tercet that concludes over the other windows: “Before there were faces . .

. / Before there were mirrors . . . /

There was water.” Most likely he’s not looking at the fish or his own

reflection, but rather at the letters attached to the concrete wall. The “h” in

“there,” the “e” in “faces,” and one of the dots from the ellipses have fallen

away.

According to the WATER website, an active water education program with classes and field trips thrives here, tours explain the remediation process, public activities flourish, couples even come here to get married. They’ve got that keeping-busy part covered, but then there’s the issue of those missing letters and what they signify. The general sense of the place suggests someone whispering, “We’ve run out of money” or “We decided to spend our money on something else.” If that’s the case, it’s a damn shame because if it all is allowed to go to seed, something more than an attractive public space will be lost.

Cleaned water flows from the treatment center and is set free—through a series of water features in various attitudes of falling and splashing, into a small creek that passes by the plinths with Goldbarth's words, and then on to the Arkansas River. There it joins water that starts as snowmelt in the heartbreakingly beautiful mountains near Leadville, Colorado, and eventually slows to a meander through the plains. A Goldbarth poem recognizes all the meandering centuries, the river exchanging its water with the clouds, dragging soil from Kansas to Napoleon, Arkansas, and there turning it over to the Mississippi to take it on to the Delta. In a trenchant installation, water falls over letters set into a weathered vertical wall:

According to the WATER website, an active water education program with classes and field trips thrives here, tours explain the remediation process, public activities flourish, couples even come here to get married. They’ve got that keeping-busy part covered, but then there’s the issue of those missing letters and what they signify. The general sense of the place suggests someone whispering, “We’ve run out of money” or “We decided to spend our money on something else.” If that’s the case, it’s a damn shame because if it all is allowed to go to seed, something more than an attractive public space will be lost.

Cleaned water flows from the treatment center and is set free—through a series of water features in various attitudes of falling and splashing, into a small creek that passes by the plinths with Goldbarth's words, and then on to the Arkansas River. There it joins water that starts as snowmelt in the heartbreakingly beautiful mountains near Leadville, Colorado, and eventually slows to a meander through the plains. A Goldbarth poem recognizes all the meandering centuries, the river exchanging its water with the clouds, dragging soil from Kansas to Napoleon, Arkansas, and there turning it over to the Mississippi to take it on to the Delta. In a trenchant installation, water falls over letters set into a weathered vertical wall:

Moving from one text to another, one begins to understand

what a large thing Goldbarth has managed to accomplish once he was freed from

the usual 8 ½ x 11 boundaries to create poetry on a codex without limits. On

opposing sides of the building’s frieze:

~The life of water never ends~

~The tear and the ocean are sisters~

Intended to serve as an introduction to the poetic project,

the following piece is cast on a plaque set into a native boulder at the park’s

entrance:

The geology-water exists among stones.

The mythology-water exists in hearts.

We’re born of them. We’re born

of all of the waters;

the Genesis-water and the Darwin-water,

the water that turns the mill,

as well as the theoretical water in clouds.

It’s 74% of our bodies.

The tear and the ocean are sisters.

The mythology-water exists in hearts.

We’re born of them. We’re born

of all of the waters;

the Genesis-water and the Darwin-water,

the water that turns the mill,

as well as the theoretical water in clouds.

It’s 74% of our bodies.

The tear and the ocean are sisters.

In Goldbarth’s hands, a landscape of poetry has become part

of the environment it interprets while it asserts, through the endless life of

water, a universal interconnecting of all things over all time.