On

17 January 2015, the Poplar pipeline, which transports 42,000 barrels of crude

oil a day under the Yellowstone River, failed, dumping an estimated 50,000

gallons of crude into the river. This is Montana’s second recent pipeline

failure; three years ago 63,000 gallons polluted Yellowstone’s water. This last

breach occurred seventeen miles upstream from Glendive, Montana, where

cancer-causing benzene was detected in the city’s water supply. Another twenty

miles or so upriver from the spill is the proposed site where the Keystone XL

pipeline will pass under the river.

Major

news sources like CNN and Fox weren’t able to see the connection, and neither,

obviously, were the politicians who approved funding for the Keystone XL

pipeline twelve days after the Glendive accident. A rancher whose land borders

the spill site had a closer, better view. Her take is tough and true: “Pipelines

leak and pipelines break. We’re never going to get around that. We have to

decide if water is more valuable than oil.” The headline for the Associated

Press story was probably more hopeful than accurate. “Montana Oil Spill

Renews Worries Over Pipeline Safety.”

Another

headline from another time comes to mind: the lead story of the 18 May 2000

issue of Glendive’s weekly, the Ranger-Review,

“Anglers But No Fish,” and the subhead “Paddlefish wait for river to rise.”

This was my first trip to a town where the week’s most important news story was

about fish waiting for something to happen. The story clarified things: “Forty

percent of the snowpack is left in the mountains, and when that melts and the

river swells, there may be one or two good weeks of paddlefishing here.”

As

it turns out, I was wondering where the

paddlefish were. I had driven to the Intake Diversion Dam about fifteen miles

downriver from Glendive because a student had told me about the tradition and

spectacle of paddlefishing and had given me a pamphlet from the Montana

Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks about Polyodon spatula that zoomed it to the top of my fish list.

“CHARACTERISTICS: Body naked except for scales on upper lobe of tail. Lobes of

tail fin unequal in size. Skeleton largely of cartilage. HABITAT: Slow or quiet

bars of large rivers during spring high water. STATUS: Native. SIMILAR SPECIES:

None.” None indeed.

This

is one strange, pre-historic-looking fish. The body is reminiscent of a

shark’s, cartilaginous and with a large, lobed tail. The mouth is remarkably

cavernous. And then there’s the snout — the rostrum, the spatula, the paddle.

It’s huge, up to two feet, sometimes making up about a quarter of the fish’s

length. It is thought to contain thousands of receptors for positioning in

shifting currents and over varied river-bottom topography. A paddlefish feeds

by sucking in water through its mouth and sifting out zooplankton with its

gills. Because of this, it rises to no bait; it must be snagged. So the fishing

technique is as distinctive as the fish. Anglers line the river, armed with

saltwater surfcasting poles with sixty-pound test line. At the end of the line

is a six-ounce weight and a treble hook tied about a foot above it. Cast it out

and pull it back with a series of hearty yanks. Hope.

The

fishing grounds without the paddlefish are without fanfare: a flood plain, a

campground with a few trailers and campers scattered among its cottonwoods, a

dusty parking lot with a half-dozen pickups. On that day of the disappointing

headline, the Yellowstone hurried along, breaking up into rapids at the dam. White

pelicans floated there or stood on the rocks. A man and a woman sitting on

overturned buckets watched their lines disappear into the café-au-lait water.

Robins chirped. Bass notes from a stereo in the campground thumped. At the edge

of a dusty bluff that overlooks the scene, is a commemorative plaque. Years ago

a young man from out of town, perhaps not river-wise, had waded out too far,

slipped on the muddy river bottom, and was carried away downstream. On the

plaque was a picture of a boy in a basketball uniform and an inscription that

declared he had “lost his beautiful life to the Yellowstone River while

paddlefishing.”

What

to do when snow won’t melt and fish won’t migrate to fit my schedule? Drive the

six hours to Yellowstone Park where the Yellowstone River runs clear and fast

and anglers gently drop their feathery lures and pause over the colors of the

trout they catch and release. Hike a week in the mountains while the paddlefish

wait for the ancient command and people come to the riverbank at Intake, eager,

then disappointed.

~

A

week gone and the word is out: the paddlefish are running. The Yellowstone at

Intake is just as brown but more agitated and higher on its banks. Anglers have

replaced the pelicans, lining the shore and milling around the riverbank. A

huge fire burns in a firepit to keep away the gnats. Nearby, people crowd a

concession stand. Kid in strollers, moms, dogs. Two anglers, call them snaggers:

George (his name is on his shirt pocket) and Leroy (a crowd favorite). Both

have the gait and legs of men who have spent a good part of their lives on

horseback. They cast out as far as they can, turn their poles to 9:00, and

begin to retrieve: pull, reel in, pull again. Each pull bends their huge

surfcasting poles double, the reeling is frantic.

George

snags his fish first. His playing of it is hard and aggressive, much like an

ocean surfcaster landing a striped bass. In fifteen minutes the paddlefish tires

and lies struggling about ten feet offshore. Someone takes George’s gaff, wades

into the river, gaffs the fish, and pulls it ashore. Used up, it lolls among

the beached logs and other detritus of the Yellowstone in spring. George

untangles his line, attaches a tag, sticks the gaff into the gills, and bends

to the difficult job of dragging fifty pounds of fish one-hundred yards up the

riverbank to the cleaning trailer. The fish’s body leaves behind a meandering

furrow in the mud and silt.

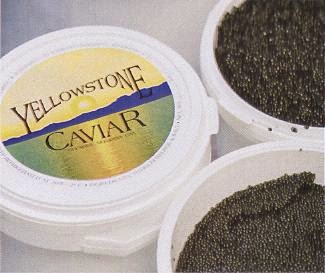

Here

at the cleaning trailer is another unique feature of Glendive paddlefishing. If

it’s not a catch-and-release day, they clean and dress each fish in exchange

for the roe, which is donated to the Glendive Chamber of Commerce and

Agriculture. The chamber processes it into caviar to sell worldwide. In the

first nine years of the program more than a million dollars were realized. This

money is divided roughly in half between the Montana Department of Fish,

Wildlife and Parks (FWP) and the chamber. FWP money is used for paddlefish

research and fishing site improvements. The chamber awards its money in grants

to nonprofit organizations for cultural, historical, or recreational projects.

Meanwhile,

back on the river, Leroy has begun an adventure with Hemingway overtones. Either

because he has snagged a larger fish, or because he has lighter line, or simply

because he prefers to, he allows fish and current their way. His technique

seems more a river technique: tip up and line taut, walk downstream, and avoid

other anglers and a temporary dock. To cheers of “go get ’em Leroy,” he disappears

around a bend about 300 yards downstream from where he got his hit.

It’s

not a pretty scene. Nobody wears Oakley sunglasses, Patagonia shorts, or Nike

water sandals. Those who have waded into a swift and silty stream with their

clothes on know what it does to shoes and socks and jeans. And a paddlefish is

so unlovely—a gray, scaleless thing that looks a bit like a shark with a canoe

paddle rammed down its throat. At the weigh-in area George is having his

picture taken with his fish hanging beside him. “Turn it around, George, you’ve

got the dirty side toward me.” And from the cleaning trailer, “Hurry up and get

that fish in here, George, I haven’t killed a thing all day.” The banter acknowledges,

celebrates, the grittiness of what is going on. No one will write a novel about

paddlefishing that will be made into a movie.

It’s

this simple. Sexually mature paddlefish migrate from Lake Sakakawea in North

Dakota — up the Missouri to the Yellowstone to reach the flowing water and

clean gravel they need for egg incubation. On the way they confront the Intake Dam,

which diverts part of the river’s flow for irrigation; some years they stack up

there by the thousands. These ancient fish wait each spring for the snow melt

and the river’s renewal to stir a community into action: action of reunion with

friends and family, action of stewardship to the river and its inhabitants. And

they stir Glendive to memory: of stories of fish caught and lost, of Leroy’s

fishing style, of a young basketball player drowned in the river, of a tie

between a community and the land it inhabits.

~

Unless

another unarmed youth is shot or another school-full of girls is kidnapped,

media interest in a story wanes after a week or so. Lacking a second accidental

oil release, the Poplar spill is quickly fading into memory. Glendive water has

been pronounced safe, the Keystone pipeline “debate” ignored 50,000 gallons of

oil in the Yellowstone, and all’s well in the world of Big Oil and politics.

Two weeks after the incident, however, damage to the river’s living inhabitants

remains unknown.

Given

a society with an ephemeral attention span, a grotesquely delusional

comprehension of time is to be expected. Paddlefish have changed little in the

last 70-75 million years. The approximate age of the Yellowstone River near

Glendive is 20,000 years, and during that time it has been alluvial, which

means it flows through the sediment that it deposits itself. In other words, it

has been constantly shifting, redefining itself over time. In this shifting

river bottom, the Poplar pipeline was buried in 1967. The question of how the

pipeline’s owners perceive time seems rather important, and, unfortunately, the

answer is at hand.

The

leaking pipe is owned by the Poplar Pipeline System, which is owned by Bridger

Pipeline, a limited liability company that is part of True Companies, a

conglomerate of companies that specialize in all things oil: pipeline,

transportation, exploration, and oilfield equipment companies. Here’s Henry “Tad”

True, Vice President of Bridger Pipeline, speaking at the 2012 Republican National

Convention:

“I

am part of the third generation of family-owned businesses, and we operate

pipelines in the great states of Wyoming, North Dakota, and Montana. These

companies were started by my grandfather, and then run by my father and my

uncles. . . . My hope is that my 3 boys — Henry, Sam, and Charlie — will be

part of the fourth generation of our family business. And although my kids

think pipelines are boring, I know and you know that Mitt Romney knows that

pipelines are vital to America’s energy system.”

Okay.

Now we know how far ahead Tad (and probably Mitt Romney) is thinking: Just as

long as my kids get their share of the wealth. This from the head of a company

that is slated to, as he said in that same speech, “build an on-ramp” to the

Keystone XL pipeline. This from the leader of a company that, according to its

hometown newspaper “. . . has a checkered environmental history, spanning 30

oil spills, multiple federal fines and a warning that the pipeline firm did not

learn from past mistakes.”

Only

a radical change of perspective can reverse what is clearly a treacherous downward

course of wrong-headed thinking. One such worldview — from 500 years ago or

more — is provided by the Great Law of Peace, the founding constitution of the

Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy. Originally an oral tradition codified in

wampum belts and then eventually committed to English, it states that all

deliberations and decisions must turn from self-interest to that of “the whole

people” and “the unborn of the future Nation” — to the community and coming

generations. Later interpretations have set the number of generations at seven.

Tad

True will spend all he wants to spend of the money he makes building the “on-ramp.”

So, doubtless, will his three sons. But sometime within seven generations, the

Keystone XL pipeline will surely burst. Just as in other rural locales across

North America, an increasingly rare sense of place and community is threatened

in Glendive. A community that could

boast they had, as one civic leader put it, “turned fish eggs into baseball

uniforms and museum exhibits” will eventually be forced to choose between oil

and water.

*******

*The Yellowstone caviar image is from midrivers.com.

**Casper (WY) Star-Tribune