Well, Consider This

Sunday, February 28, 2016

Monday, October 12, 2015

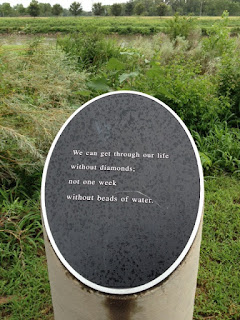

The Life of Water, Poetry without Borders

This story will meander in the fashion of the river that

provides its background, but it begins with a tableau. Wichita-based poet

Albert Goldbarth stands overlooking a waist-high plinth and beyond—to the

Arkansas (accent on the second syllable) River toward what used to be New Spain

but is now South Wichita. It’s raining on Albert and the plinth and the rest of

us. He’s standing under one of those MOMA catalog umbrellas, the one with the

image of fluffy white clouds and blue sky on the underside so that he's always

in fair weather. As must be the case for anything to be interesting, incoming

information here is complex and contradictory. The words cast on the

rain-spattered plinth are Albert's.

Trichloroethene (a.k.a. Tricky) was first produced in the 1920s and used as an invaluable field hospital anesthetic during World War II—invaluable because it didn't seem to attack a patient's liver as chloroform does or tend to blow up like ether. However, as is the case with a lot of things that look good during wars but later on turn out otherwise (DDT is a great example), Tricky revealed its nasty self to be toxic and carcinogenic; its use in the food and pharmaceutical industries has been banned in much of the world since the 1970s. Tricky has persevered, however, as a heavy-duty degreaser.

In 1991, Trichloroethene—along with a carcinogenic and toxic posse including

Tetrachloroethene (dry-cleaning fluid), 1,2-Dichloroethene, and good old vinyl chloride—was found in the groundwater in a 5 ½ square mile area under downtown Wichita, a few blocks north of the Goldbarth/umbrella/Arkansas River scene. Immediately everyone did what good civic and business leaders do—they hastened to assign blame, threaten litigation, and figure out how to avoid a cash hemorrhage. Eventually the federal government intervened with the threat of a Superfund site and its attendant baggage, and out of desperation—and ten years after the contamination was discovered—Wichita created WATER, the Wichita Area Treatment, Education & Remediation Center, which sounds more like a substance abuse treatment hospital. And of course, in a way, it is.

Contaminated groundwater is gathered through extraction wells and miles of piping, treated and remediated at the WATER site, and released into the Arkansas. The vision for the treatment facility included the city park where it was located and the notion of a social and educational public place. Realizing that a world-class poet lived in town, planners advanced the idea of a rather implausible wedding of poetry and hydrology. As a happy result, paths meander through park landscaping and lead walkers past other plinths, each displaying four Goldbarth lines, expressions of the pervasive interconnection of humans and their environment. On one, the trees remind readers "Like you, we're silos of water," on another, "The life of water never ends / it merely has different bodies." Here’s a third:

In a second set piece, Goldbarth is standing before one of

three observation windows that are built into a wall of the treatment facility

and that provide a cloudy view of an aquarium featuring native Kansas fish.

Next to the reflection of the poet’s head, a good-sized sunfish floats

motionless. Above the window is more Goldbarth language, the first line of a

tercet that concludes over the other windows: “Before there were faces . .

. / Before there were mirrors . . . /

There was water.” Most likely he’s not looking at the fish or his own

reflection, but rather at the letters attached to the concrete wall. The “h” in

“there,” the “e” in “faces,” and one of the dots from the ellipses have fallen

away.

According to the WATER website, an active water education program with classes and field trips thrives here, tours explain the remediation process, public activities flourish, couples even come here to get married. They’ve got that keeping-busy part covered, but then there’s the issue of those missing letters and what they signify. The general sense of the place suggests someone whispering, “We’ve run out of money” or “We decided to spend our money on something else.” If that’s the case, it’s a damn shame because if it all is allowed to go to seed, something more than an attractive public space will be lost.

Cleaned water flows from the treatment center and is set free—through a series of water features in various attitudes of falling and splashing, into a small creek that passes by the plinths with Goldbarth's words, and then on to the Arkansas River. There it joins water that starts as snowmelt in the heartbreakingly beautiful mountains near Leadville, Colorado, and eventually slows to a meander through the plains. A Goldbarth poem recognizes all the meandering centuries, the river exchanging its water with the clouds, dragging soil from Kansas to Napoleon, Arkansas, and there turning it over to the Mississippi to take it on to the Delta. In a trenchant installation, water falls over letters set into a weathered vertical wall:

According to the WATER website, an active water education program with classes and field trips thrives here, tours explain the remediation process, public activities flourish, couples even come here to get married. They’ve got that keeping-busy part covered, but then there’s the issue of those missing letters and what they signify. The general sense of the place suggests someone whispering, “We’ve run out of money” or “We decided to spend our money on something else.” If that’s the case, it’s a damn shame because if it all is allowed to go to seed, something more than an attractive public space will be lost.

Cleaned water flows from the treatment center and is set free—through a series of water features in various attitudes of falling and splashing, into a small creek that passes by the plinths with Goldbarth's words, and then on to the Arkansas River. There it joins water that starts as snowmelt in the heartbreakingly beautiful mountains near Leadville, Colorado, and eventually slows to a meander through the plains. A Goldbarth poem recognizes all the meandering centuries, the river exchanging its water with the clouds, dragging soil from Kansas to Napoleon, Arkansas, and there turning it over to the Mississippi to take it on to the Delta. In a trenchant installation, water falls over letters set into a weathered vertical wall:

Moving from one text to another, one begins to understand

what a large thing Goldbarth has managed to accomplish once he was freed from

the usual 8 ½ x 11 boundaries to create poetry on a codex without limits. On

opposing sides of the building’s frieze:

~The life of water never ends~

~The tear and the ocean are sisters~

Intended to serve as an introduction to the poetic project,

the following piece is cast on a plaque set into a native boulder at the park’s

entrance:

The geology-water exists among stones.

The mythology-water exists in hearts.

We’re born of them. We’re born

of all of the waters;

the Genesis-water and the Darwin-water,

the water that turns the mill,

as well as the theoretical water in clouds.

It’s 74% of our bodies.

The tear and the ocean are sisters.

The mythology-water exists in hearts.

We’re born of them. We’re born

of all of the waters;

the Genesis-water and the Darwin-water,

the water that turns the mill,

as well as the theoretical water in clouds.

It’s 74% of our bodies.

The tear and the ocean are sisters.

In Goldbarth’s hands, a landscape of poetry has become part

of the environment it interprets while it asserts, through the endless life of

water, a universal interconnecting of all things over all time.

Friday, June 5, 2015

Ephemera in the Woods

In one of Wallace Stevens' best-known poems, the speaker places a jar on a hill in Tennessee. “It made the

slovenly wilderness / Surround that hill. // The wilderness rose up to it, / And

sprawled around, no longer wild.” In Levitated

Mass, one of Michael Heizer’s best known art works, he “placed” a 340-ton

boulder over a below-ground walkway in Los Angeles. A little closer to Athens,

Georgia, over the past several weeks, people walking the trails at the State Botanical

Garden of Georgia have noticed long rows of fallen branches running parallel to

the paths. At first these seemed to be arbitrary piles of woodsy flotsam

perhaps gathered up by some whimsical workers among the many volunteers that

help maintain the place. But the number of windrows increased and they acquired

the suggestion of order, appearing to run along hillsides like contour lines on

a topo map. And then the first structure (a circle about

four feet in diameter, two feet high, and constructed from small logs and

branches) appeared near one of the trails. Then a second in another section of the grounds.

The structures, I've since discovered, are the work of Athens-based land artist Chris Taylor, who plans at least two dozen. When completed, they will comprise "Garden Nests: An ephemeral and exertive interpretation of home." It's an installation, in the words of the artist, "illustrating Athens as both a permanent home to its residents, and a transient home for students, teachers, artists, musicians, scientists, and the like. Whether temporary or for a lifetime, the home you create is suited to your needs, using what's around you, and moved if necessary. Anyone can create a home with the right opportunity and accessibility."

The structures, I've since discovered, are the work of Athens-based land artist Chris Taylor, who plans at least two dozen. When completed, they will comprise "Garden Nests: An ephemeral and exertive interpretation of home." It's an installation, in the words of the artist, "illustrating Athens as both a permanent home to its residents, and a transient home for students, teachers, artists, musicians, scientists, and the like. Whether temporary or for a lifetime, the home you create is suited to your needs, using what's around you, and moved if necessary. Anyone can create a home with the right opportunity and accessibility."

As does any

construct in nature—a jar on a hillside in Tennessee, a suspended boulder

outside the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, a spiral jetty extending into

Great Salt Lake, six miles of silver fabric hanging over the Arkansas River, or

a pyramid near El Giza, Egypt—"Garden Nests" invites a close look at the forms that human

culture imposes on the natural world and the artistic statements that result.

In his fine essay in The Georgia Review’s Fall 2008 issue, “Forms

and Structures,” Stephen Dunn quotes his own—considerably shorter—“Little

Essay on Form” in its entirety: “We build the corral as we reinvent the horse.”

Leave it to a poet to nail a metaphor so well, a metaphor that can withstand

being poked and prodded until it reveals its depth and weight.

Among the examples Dunn employs is

the work of Scottish sculptor and photographer Andy Goldsworthy, who for the

last four decades has created forms from natural objects and enacted moments

that for him embody past, present, and future time. Goldsworthy’s work ranges

anywhere from small and ephemeral designs of autumn leaves laid out on an open

hillside, to lines of connected grasses set adrift in a stream, to

near-monumental stone arches—seemingly just about any creation imaginable,

idiosyncratic, and innovative.

Goldsworthy’s goal is to understand

the natural world through touch, to work with the qualities of any given

material, to understand the material’s place by engaging with its qualities and

its history, and ultimately, as an artist, to create a form, to build Dunn’s corral for a new way of seeing: colored leaves as palate, icicles as

prisms, fallen branches as walls. Heizer has famously said: “I’m self-entertaining. My dialog is

with myself.” Goldsworthy too. Much of what is derived from his art is his own.

What he learns of rock from balancing one on another, of cold by crafting

shapes from icicles, of gravity by building a doorway of twigs, of snow by

throwing it into the wind—all this knowledge is Goldsworthy’s and his alone. For

someone seeing images of his work or those lucky enough to visit the more permanent

sites, Goldsworthy’s attention to the traditions of art reveal a primarily

modernist aesthetic. The nature of his structures provides the connection.

By way of example, consider

Goldsworthy’s 1999 construction of a driftwood dome at the mouth of an estuary

near Halifax, Nova Scotia. Ideally, a place will suggest to him what direction the

work will take. So when his introduction to the beach was “a river and a pool

that was being turned by the river,” he saw immediately the potential: on a

rising tide, a confluence of “two energies at the powerful moment when the sea

and river meet.” To understand this moment, he began to replicate what he

called the “turning pool” by gathering bleached driftwood to build a dome on

the rocky shore beside the pool. Working

from inside, he placed the driftwood in a circular motion until it reached about six

feet high, then crawled out the bottom. He left an opening in the top—because

looking into a hole makes him “. . . aware of the potent energies within the earth.”

Then he waited for the moment when the

energies of the sea, the river, and the earth would come together.

Goldsworthy’s work focuses on such moments, but all of his materials—that is, elements

of the natural world—will persist in some form and, prior to his intervention,

existed in yet another. As he says, “The more I worked, the more aware I became

of the powerful sense of time embedded in place. The moment of my working a

material and of my being there was bound up with what had gone before.” The

future, on the other hand, is a lesson in impermanence.

The moment arrived. When the

incoming tide reached the turning pool and the dome, it first pulled the lowest

sticks away. Then it lifted the entire structure and began to turn it just as

the river is turned twice each day. Finally the tide pulled the dome free of

the pool and carried it slowly upstream. Goldsworthy recalled his feelings

watching the dome drift away as it foundered gently: “It feels like it’s being

taken off into another plane, into another world or another work. It doesn’t

feel at all like destruction. It feels as if you’ve touched the heart of the

place. That’s the way of understanding, seeing something you never saw before

that was always there but you were blind to it. I followed the sticks

upstream—darkness was falling—eventually leaving it to drift off into the night

towards the town.”

As Dunn asserts, “Essentially, form’s

job is to help reveal content. . . . It guides the eye.” For Goldsworthy, it alters

how we understand not only the material but also the space and energy around

the material. Form, then, is the principal enabler of transformation in art.

The corral is built, the horse is reinvented. Artists build and we stand by; in

their process of creating, they give us a vantage point. What we readers and

viewers do with the experience is up to us. As I watched film of Goldsworthy’s dome disappearing on the rising tide, I

thought about other turning forms: channel whelks, my failing ears, and—about

as far away from a cold beach in Nova Scotia as you can get—a cliff at Chaco

Canyon where Ancestral Puebloans carved the emblem of their emergence, a spiral

on a sandstone wall.

*******

Goldsworthy quotations are from Andy Goldsworthy: Rivers and Tides (Dir.

Thomas Riedelsheimer, 2001) and Andy Goldsworthy’s Time (Abrams, 2000).

Sunday, March 22, 2015

Paul Gruchow and Brian Turner: Two Memoirs Go Cubistic

This

is one possible definition of mental illness: It is the sickness of unborn

pain.

Suicide,

when it happens, is often, although I think not inevitably, tragic, but the

thought of suicide might well be a successful adaptation of the human mind to

extreme emotional distress.

It

is an odd fact that in the history of humanity that we have been dying for

millennia, without exception, and yet we still cannot face the fact that this

is not a tragedy.

Sentences like these

from Paul Gruchow’s extraordinary memoir (Letters

to a Young Madman: A Memoir, Levins Publishing, 2012) have a monumental

feel that commands special handling. Writing about big things necessitates

urgency—not to hurry the story into print but to get it told right. Sometimes

the need is so great that the customary ways just won’t do. Gruchow and Brian

Turner (My Life as a Foreign Country: A

Memoir, W.W. Norton, 2013)—as unlikely a pair of authors to appear in the

same sentence—shared that literary urgency. Gruchow, essayist lost to suicide,

and Turner, poet and Iraq war combat survivor—I bring them together here to

look at how they turned from their usual way of doing things to make their

stories into powerful memoir.

The author of six

acclaimed books of essays, Gruchow suffered through periods of depression and

hospitalization that eventually closed down his strong and often lyrical nature-writing

voice. Emerging from his protracted dry spell, however, he began work on a book

about his disease and treatment. He had accumulated pages of research,

recollections of childhood, vivid tales from inside mental institutions, even poems.

But how to fit it all into the elegantly structured essay style that had served

him over the years had him stymied and frustrated. Enter his friend and

literary confidant, Louis Martinelli, who came upon the inspired idea of

pointing Gruchow to the fragmented structure of Eduardo Galeano’s books. As

Martinelli says, “Paul got it right away.”

On the other hand, with

his reputation as a poet (Here, Bullet and

Phantom Noise) firmly in hand, Brian Turner

moved to nonfiction in a manner influenced strongly by his poetic aesthetic. In

an interview published on Brevity’s

Nonfiction Blog (23 September 2014), he told how after his military discharge

he was experimenting with haibun, a

traditional Japanese travel-writing form that combines a brief prose section

with a haiku. With no other intent (“I was simply experimenting with form and

trying to discover how it shaped my thoughts on memory and travel”), he

realized that an essay was emerging, an essay that would later grow into his

memoir of war and soldiering. The resulting fragmented work depends, in

Turner’s words, on “a reader that enjoys participating in the construction of

the work itself.” Discrete sections of narrative from across time, expository

historical sections, poetry, even a short screenplay wait to be joined by that

reader’s imagination.

Of course the notion of

assembling a myriad of referential moments isn’t new. How can any English major

forget T.S. Eliot’s “fragments” that he “shored against [his] ruins”? But the

notion is modern. Remember Tristram Shandy? Doesn’t it read,

diction aside, as though it were written a lot later than the middle of the

eighteenth century? It has that turn-of-the-twentieth-century feel to it—the

feel of that last, great epochal intellectual shift.

In 1907, Picasso set

the foundation for Cubism when he came to Paris with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the portrait of five nude prostitutes,

anatomically approximate but distorted beyond any semblance to an impressionist

or realist nude. It fell to Georges Braque to show the real meaning of Picasso’s

painting, which he did in a series of landscapes that included Houses at l’Estaque (1908). Here he

simply took apart a village visually and reassembled it as it might be seen

from multiple vantages. How does one look at five nude prostitutes anyway?

Well, look at one for a while, then another, look at parts of them that capture

your eye, turn away, turn back, left eye only, right eye, notice the setting.

Then think about how all these views make you feel. Memory and imagination will

do the rest. To paint that canvas would result in something more realistic than

any Titian.

Cezanne declared, and

Picasso and Braque echoed: Art is not nature and shouldn’t try to imitate it.

And just like that they rejected an aesthetic that had dominated visual art

since the Renaissance. After that, there

was no turning back. A painting was paint on a surface, nothing more, not a

window to the world outside. What freedom.

~

What matters is the

connection between fragmentation and memory, narrative and perception.

Modernist writing went Cubist in varying ways: Dos Passos’ “newsreels” and

“camera eyes,” William Burroughs’ “cutups,” the “things” of Paterson that contain William’s ideas,

and of course Eliot’s blend of the common and the obscure. Without the

traditional transitions, unconnected text has to be seen in visual terms in

order to be understood, must be related in ways that correspond to shape or

color or size. In other words, the organization becomes abstract, at which

point the correspondence between modern painting and modern writing is quite

apparent.

In addition, the fragments

can be seen as metaphor, attention given to the tension their various juxtapositions

create—space to be filled with something or not filled, just space to define

the actual. For what the Cubists found when they dumped 400 years of rules

about perspective was a new kind of space—what Braque called “tactile space,”

the distance between the viewer and the painting rather than the distance

between the painting’s objects. In this way, the viewer gains a new

involvement.

Whether in painting or

writing, singing or dancing, between the fragments comes space. But there’s so

much more—it’s not merely a structural thing, emptiness created by whatever

fragments or elements limit it; it is real, and it exists in time as well. As a

viewer or reader experiences those surrounding elements, whatever takes place

in that person’s imagination becomes the space.

Japanese culture has

offered a word for it. Ma. It is said

that in nothingness, ma enables. Ma is an interval, the presence of an

absence, a void waiting. And from China more than 2500 years ago,

We join spokes together in a wheel,

but it is the center hole

that makes the wagon move.

We shape clay into a pot,

but it is the emptiness inside

that holds whatever we want.

We hammer wood for a house

but it is the inner space

that makes it livable.

We work with being,

but non-being is what we use.

Lao-tzu, Tao Te Ching, Trans. Stephen Mitchell

Testimony to Gruchow’s

and Turner’s artful handling of what might at first appear to be a random or

self-indulgent structure can be found in the tight control with which each

author manages the cohesion of his book. Each fragment has been composed and

situated with an eye both to its neighbors and to its overall purpose, and an

overall unity derives from continuation—of theme and time in Gruchow’s case and

in Turner’s, of poetic and novelistic devices.

Although the overall

organization of Letters to a Young Madman—absent

the usual chapter or section demarcations—may appear arbitrary, it suggests

strongly a chronological reading. A wide range of quotations from Marcus

Aurelius to Nietzsche set off apparent section divisions, and each fragment

bears its own title. But the quotations are best read alongside Gruchow’s

fragments rather than as introductions or summations. I’m examining here a

fifteen-page section of eleven fragments located between pieces titled “The Hospital

1” and “A Modest Proposal” that highlight what elevates Letters above mere memoir: Gruchow’s ultimate aim, which is no less

than to reform the mental health system. The fragments vary in length from two

sentences to two pages, starting with a chilling recounting of the first

moments of admission for a new psychiatric hospital patient and ending with a

scathing suggestion for hospital reform.

“The Hospital 1”

describes the intake process in declarative, simple sentences, most fewer than

a dozen words. The effect is haunting.

You

are led down a long hallway to your room. The hallway is wide and barren. The room

has two beds, a window, and one, hard low-backed chair. The window is covered in

thick Plexiglas. The floor is hard and the walls are unornamented. Everything

is some shade of gray. The beds are standard hospital issue.

The voice is

deliberately child-like because, as Gruchow says, “The last time you wore

pajamas twenty-four hours a day, you were an infant. You have now assumed the

appearance of a mental patient.” The point of view throughout is second person,

and the direct address is doubled when he has a nurse speak to the patient,

“I’m sorry but you’ll have to remove your shorts too.” (You, the reader,

suddenly morphs into you, the patient, and when Gruchow tells you the blankets

are flimsy and psychiatric wards are chilly, you empathize because you’ve

walked a mile in his hospital-issue socks.

“The Hospital 2,”

written in the same, flat voice, lays out the routine. And as if Gruchow were

unable to break the old transition-sentence habit, the closing sentence—“Three

or four days of this routine and you are bored to the bones”—introduces three

short “Boredom” chapters. Here Gruchow

drops the insider voice and returns to his familiar rhythms and approach. The

comments are trenchant, the sentences exact. The pieces run from three to eight

lines each and have the same stabbing effect as short sentences surrounded by

longer ones: “Boredom 2,” for example, reads in its entirety: “Babies have

pacifiers. Adults have television. The reason the television set is in the

center of the psychiatric ward life is that watching it is the only thing in

life that requires less effort than sleeping.” He then stops to summarize in “The

Hospital 3,” a statement that should be read by anyone connected in any

conceivable way to the mental health system in this country. It’s another brief

paragraph, and he’s considering what the mental health system calls the “therapeutic

milieu.”

Reduce

an adult to the status of a child, put him in surroundings that resemble as

little as possible a home, deprive him of nearly all intellectual and sensory

stimuli, induce nicotine and caffeine withdrawal, and provoke a simultaneous

state of insomnia and intense boredom. Perhaps there is something therapeutic in

this, but I confess that I cannot see what it is. Of course, I am not a

psychiatrist.

What a gem of

controlled anger and clear insight.

In a longer narrative

that follows, Gruchow is a storyteller; then in a concise look at psychiatric

hospital design, he’s a researcher. Finally, two fragments compare and contrast

hospital and prison life in traditional rhetorical ways. If read

thoughtfully—by Turner’s ideal reader who “enjoys participating in the

construction of the work itself”—all this jumping around, changing voices, and

coming at an issue from as many angles as possible—creates discrete moments of

intense empathy and comprehension broken by intervals inviting imagination and

contemplation. To help the reader in synthesizing these fragments, Gruchow

closes the section with “A Modest Proposal,” a satirical piece worthy of the

Swift tradition. In it, he suggests that before given admission to practice,

psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses must each be admitted to a psychiatric

ward with a “particularly pejorative diagnosis,” be medicated, and be given

“two weeks to convince the staff, without reference to their credentials, that

they are sane.” Those who fail get another chance in six months. Gruchow’s

proposal is a fine piece of wit that gathers and concludes the various

fragments of the section in a truly organic way.

In My Life as a Foreign Country, Turner numbers his fragments but

otherwise eschews any explicit divisions. He also provides blank pages that serve

to separate sections as well as to create silent intervals for taking deeper

breaths, waiting for understanding. The gathering of fragments considered here

(29-40) focus on and emanate from the recruiter’s office where Turner’s

military service began. Thoroughly remembered down to the “warmth of the

freshly printed list of options,” the scene ends with the anaphoric sentence

that will function like a musical burden—a droning repetition of a refrain:

variations on the sentence, “I pointed to the list and said the word Infantry.”

Why would anyone do

such a thing? I can give you only an impression of the answer. In fragment 30,

an eleven-year-old Turner is digging a foxhole based on specifications from his

father’s infantry field manuals. “I signed the paper and joined the infantry

for reasons I won’t tell you and for reasons I will.” In fragment 32, Turner’s

father, involved in a nearly fatal motorcycle accident, is left with a story

and a huge scar. “The scar said—that which is written in the flesh is

irrefutable. This is the mark of a man. This is what it takes.” In fragment 33,

Turner and his father— “fighting the invisible before us”— train in a backyard

dojo. “I pointed to the list and said

Infantry because I wanted the man in the polyester suit to know, at some

unconscious level, that I didn’t give a shit what row of ribbons he had pinned

to his chest.” In fragment 35, Turner is making homemade napalm with his father

following a recipe from The Poor Man’s

James Bond. And he’s remembering stories: from his Vietnam Veteran uncle

about enemy interrogations, from his father about secret reconnaissance

missions.

In the midst of this

collage of memory and violence, Turner inserts the screenplay of “The War that

Time Forgot,” a Super8 movie written, produced, and acted by him and his

middle-school friends. The movie concludes when the star (Sgt. T., played by Turner),

to a background of Barber’s Adagio for Strings, blows off an enemy’s head—“a

melon filled with sheep’s blood and pig brains.”

Then Turner returns to

the stories. His father clinically dead from a heart attack, revives. “So what

was it like, dying?” Turner asks. “That,” his father answers, “ that was a

trauma-junkie’s delight.”

Fragment 39 describes a

chilling moment of epiphany.

When

we triggered the device and the napalm exploded, I felt charged and electric.

We were surrounded by the cold. Coffee steamed in the cup as the entire world

disappeared in fog. And for a moment, I knew—here was the great body of Death.

A portion of the inheritance we all share. I wanted to see it break open in fire.

I wanted the world to be shaken by it. And, most of all, I wanted to be shaken

by it, too.

In the final fragment,

Turner introduces even more accounting—to the background of the burden’s drone:

“I said Infantry because my great-grandfather Carter was gassed during the

Battle of Meuse-Argonne in the fall of 1918.” And “I said Infantry because one

of my great-greats enlisted in the Union Army—15 November 1861—at Cumberland

Gap, Tennessee. . . .” And he signed because his grandfather survived

Bougainville and Guam and Iwo Jima. “I signed the paper because I knew that on

some deep and immutable level, I would leave and I would never come back.”

Of course, no

definitive explanation of Turner’s choices exists, but an empathic reading is

possible. It lies in the spaces between the fragments of his recollections,

just beyond language but informed by it. In the same way, Paul Gruchow’s

accounts

of the suffering the mentally ill endure and his rendering of his own struggle with

mental illness are so powerful that his words and images remain with us as we

pause, engage our own imaginations, and begin to understand during his book’s

indwelling silences.

********

This piece appeared first in Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies (1.2). Check their website to see the good company it's keeping there.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon from moma.org.

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Turning Fish Eggs into Baseball Uniforms

On

17 January 2015, the Poplar pipeline, which transports 42,000 barrels of crude

oil a day under the Yellowstone River, failed, dumping an estimated 50,000

gallons of crude into the river. This is Montana’s second recent pipeline

failure; three years ago 63,000 gallons polluted Yellowstone’s water. This last

breach occurred seventeen miles upstream from Glendive, Montana, where

cancer-causing benzene was detected in the city’s water supply. Another twenty

miles or so upriver from the spill is the proposed site where the Keystone XL

pipeline will pass under the river.

Major

news sources like CNN and Fox weren’t able to see the connection, and neither,

obviously, were the politicians who approved funding for the Keystone XL

pipeline twelve days after the Glendive accident. A rancher whose land borders

the spill site had a closer, better view. Her take is tough and true: “Pipelines

leak and pipelines break. We’re never going to get around that. We have to

decide if water is more valuable than oil.” The headline for the Associated

Press story was probably more hopeful than accurate. “Montana Oil Spill

Renews Worries Over Pipeline Safety.”

Another

headline from another time comes to mind: the lead story of the 18 May 2000

issue of Glendive’s weekly, the Ranger-Review,

“Anglers But No Fish,” and the subhead “Paddlefish wait for river to rise.”

This was my first trip to a town where the week’s most important news story was

about fish waiting for something to happen. The story clarified things: “Forty

percent of the snowpack is left in the mountains, and when that melts and the

river swells, there may be one or two good weeks of paddlefishing here.”

As

it turns out, I was wondering where the

paddlefish were. I had driven to the Intake Diversion Dam about fifteen miles

downriver from Glendive because a student had told me about the tradition and

spectacle of paddlefishing and had given me a pamphlet from the Montana

Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks about Polyodon spatula that zoomed it to the top of my fish list.

“CHARACTERISTICS: Body naked except for scales on upper lobe of tail. Lobes of

tail fin unequal in size. Skeleton largely of cartilage. HABITAT: Slow or quiet

bars of large rivers during spring high water. STATUS: Native. SIMILAR SPECIES:

None.” None indeed.

This

is one strange, pre-historic-looking fish. The body is reminiscent of a

shark’s, cartilaginous and with a large, lobed tail. The mouth is remarkably

cavernous. And then there’s the snout — the rostrum, the spatula, the paddle.

It’s huge, up to two feet, sometimes making up about a quarter of the fish’s

length. It is thought to contain thousands of receptors for positioning in

shifting currents and over varied river-bottom topography. A paddlefish feeds

by sucking in water through its mouth and sifting out zooplankton with its

gills. Because of this, it rises to no bait; it must be snagged. So the fishing

technique is as distinctive as the fish. Anglers line the river, armed with

saltwater surfcasting poles with sixty-pound test line. At the end of the line

is a six-ounce weight and a treble hook tied about a foot above it. Cast it out

and pull it back with a series of hearty yanks. Hope.

The

fishing grounds without the paddlefish are without fanfare: a flood plain, a

campground with a few trailers and campers scattered among its cottonwoods, a

dusty parking lot with a half-dozen pickups. On that day of the disappointing

headline, the Yellowstone hurried along, breaking up into rapids at the dam. White

pelicans floated there or stood on the rocks. A man and a woman sitting on

overturned buckets watched their lines disappear into the café-au-lait water.

Robins chirped. Bass notes from a stereo in the campground thumped. At the edge

of a dusty bluff that overlooks the scene, is a commemorative plaque. Years ago

a young man from out of town, perhaps not river-wise, had waded out too far,

slipped on the muddy river bottom, and was carried away downstream. On the

plaque was a picture of a boy in a basketball uniform and an inscription that

declared he had “lost his beautiful life to the Yellowstone River while

paddlefishing.”

What

to do when snow won’t melt and fish won’t migrate to fit my schedule? Drive the

six hours to Yellowstone Park where the Yellowstone River runs clear and fast

and anglers gently drop their feathery lures and pause over the colors of the

trout they catch and release. Hike a week in the mountains while the paddlefish

wait for the ancient command and people come to the riverbank at Intake, eager,

then disappointed.

~

A

week gone and the word is out: the paddlefish are running. The Yellowstone at

Intake is just as brown but more agitated and higher on its banks. Anglers have

replaced the pelicans, lining the shore and milling around the riverbank. A

huge fire burns in a firepit to keep away the gnats. Nearby, people crowd a

concession stand. Kid in strollers, moms, dogs. Two anglers, call them snaggers:

George (his name is on his shirt pocket) and Leroy (a crowd favorite). Both

have the gait and legs of men who have spent a good part of their lives on

horseback. They cast out as far as they can, turn their poles to 9:00, and

begin to retrieve: pull, reel in, pull again. Each pull bends their huge

surfcasting poles double, the reeling is frantic.

George

snags his fish first. His playing of it is hard and aggressive, much like an

ocean surfcaster landing a striped bass. In fifteen minutes the paddlefish tires

and lies struggling about ten feet offshore. Someone takes George’s gaff, wades

into the river, gaffs the fish, and pulls it ashore. Used up, it lolls among

the beached logs and other detritus of the Yellowstone in spring. George

untangles his line, attaches a tag, sticks the gaff into the gills, and bends

to the difficult job of dragging fifty pounds of fish one-hundred yards up the

riverbank to the cleaning trailer. The fish’s body leaves behind a meandering

furrow in the mud and silt.

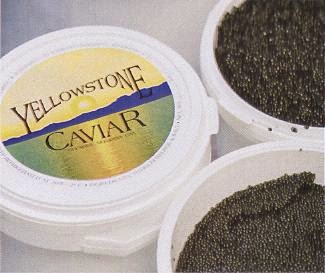

Here

at the cleaning trailer is another unique feature of Glendive paddlefishing. If

it’s not a catch-and-release day, they clean and dress each fish in exchange

for the roe, which is donated to the Glendive Chamber of Commerce and

Agriculture. The chamber processes it into caviar to sell worldwide. In the

first nine years of the program more than a million dollars were realized. This

money is divided roughly in half between the Montana Department of Fish,

Wildlife and Parks (FWP) and the chamber. FWP money is used for paddlefish

research and fishing site improvements. The chamber awards its money in grants

to nonprofit organizations for cultural, historical, or recreational projects.

Meanwhile,

back on the river, Leroy has begun an adventure with Hemingway overtones. Either

because he has snagged a larger fish, or because he has lighter line, or simply

because he prefers to, he allows fish and current their way. His technique

seems more a river technique: tip up and line taut, walk downstream, and avoid

other anglers and a temporary dock. To cheers of “go get ’em Leroy,” he disappears

around a bend about 300 yards downstream from where he got his hit.

It’s

not a pretty scene. Nobody wears Oakley sunglasses, Patagonia shorts, or Nike

water sandals. Those who have waded into a swift and silty stream with their

clothes on know what it does to shoes and socks and jeans. And a paddlefish is

so unlovely—a gray, scaleless thing that looks a bit like a shark with a canoe

paddle rammed down its throat. At the weigh-in area George is having his

picture taken with his fish hanging beside him. “Turn it around, George, you’ve

got the dirty side toward me.” And from the cleaning trailer, “Hurry up and get

that fish in here, George, I haven’t killed a thing all day.” The banter acknowledges,

celebrates, the grittiness of what is going on. No one will write a novel about

paddlefishing that will be made into a movie.

It’s

this simple. Sexually mature paddlefish migrate from Lake Sakakawea in North

Dakota — up the Missouri to the Yellowstone to reach the flowing water and

clean gravel they need for egg incubation. On the way they confront the Intake Dam,

which diverts part of the river’s flow for irrigation; some years they stack up

there by the thousands. These ancient fish wait each spring for the snow melt

and the river’s renewal to stir a community into action: action of reunion with

friends and family, action of stewardship to the river and its inhabitants. And

they stir Glendive to memory: of stories of fish caught and lost, of Leroy’s

fishing style, of a young basketball player drowned in the river, of a tie

between a community and the land it inhabits.

~

Unless

another unarmed youth is shot or another school-full of girls is kidnapped,

media interest in a story wanes after a week or so. Lacking a second accidental

oil release, the Poplar spill is quickly fading into memory. Glendive water has

been pronounced safe, the Keystone pipeline “debate” ignored 50,000 gallons of

oil in the Yellowstone, and all’s well in the world of Big Oil and politics.

Two weeks after the incident, however, damage to the river’s living inhabitants

remains unknown.

Given

a society with an ephemeral attention span, a grotesquely delusional

comprehension of time is to be expected. Paddlefish have changed little in the

last 70-75 million years. The approximate age of the Yellowstone River near

Glendive is 20,000 years, and during that time it has been alluvial, which

means it flows through the sediment that it deposits itself. In other words, it

has been constantly shifting, redefining itself over time. In this shifting

river bottom, the Poplar pipeline was buried in 1967. The question of how the

pipeline’s owners perceive time seems rather important, and, unfortunately, the

answer is at hand.

The

leaking pipe is owned by the Poplar Pipeline System, which is owned by Bridger

Pipeline, a limited liability company that is part of True Companies, a

conglomerate of companies that specialize in all things oil: pipeline,

transportation, exploration, and oilfield equipment companies. Here’s Henry “Tad”

True, Vice President of Bridger Pipeline, speaking at the 2012 Republican National

Convention:

“I

am part of the third generation of family-owned businesses, and we operate

pipelines in the great states of Wyoming, North Dakota, and Montana. These

companies were started by my grandfather, and then run by my father and my

uncles. . . . My hope is that my 3 boys — Henry, Sam, and Charlie — will be

part of the fourth generation of our family business. And although my kids

think pipelines are boring, I know and you know that Mitt Romney knows that

pipelines are vital to America’s energy system.”

Okay.

Now we know how far ahead Tad (and probably Mitt Romney) is thinking: Just as

long as my kids get their share of the wealth. This from the head of a company

that is slated to, as he said in that same speech, “build an on-ramp” to the

Keystone XL pipeline. This from the leader of a company that, according to its

hometown newspaper “. . . has a checkered environmental history, spanning 30

oil spills, multiple federal fines and a warning that the pipeline firm did not

learn from past mistakes.”

Only

a radical change of perspective can reverse what is clearly a treacherous downward

course of wrong-headed thinking. One such worldview — from 500 years ago or

more — is provided by the Great Law of Peace, the founding constitution of the

Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy. Originally an oral tradition codified in

wampum belts and then eventually committed to English, it states that all

deliberations and decisions must turn from self-interest to that of “the whole

people” and “the unborn of the future Nation” — to the community and coming

generations. Later interpretations have set the number of generations at seven.

Tad

True will spend all he wants to spend of the money he makes building the “on-ramp.”

So, doubtless, will his three sons. But sometime within seven generations, the

Keystone XL pipeline will surely burst. Just as in other rural locales across

North America, an increasingly rare sense of place and community is threatened

in Glendive. A community that could

boast they had, as one civic leader put it, “turned fish eggs into baseball

uniforms and museum exhibits” will eventually be forced to choose between oil

and water.

*******

*The Yellowstone caviar image is from midrivers.com.

**Casper (WY) Star-Tribune

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

Seventy Years of Diphthongs and Buttery Long Vowels

Donald

Hall’s new collection of essays, Essays

After Eighty, came out a couple weeks ago. “Oh frabjous day!” Let’s be

honest, we had given the man up for dead more than twenty years past when his

colon cancer metastasized to his liver. He survived that to endure the

horrendous loss of Jane Kenyon. Then, in his words, poetry abandoned him (Poetry is sex, according to the Donald Hall Lost Muse

Theorem; sex requires testosterone; testosterone decreases with age). So he was

left to write prose in his celebrated blue chair by the window; then, with one

of his stupid cigarettes, he accidentally set fire to the blue chair, which was

hauled outside and put to death by axe-wielding firemen. Old age, as he writes,

is “a ceremony of losses.”

I admit

to a weakness for Hall’s prose, partly because of what he did to mine years

ago. He pared and whittled my essays and helped me understand the delights of

revision. But he turned me into such a slavish disciple that he finally said, “Don’t

let me turn your prose into a telegram.” I think most writers write — whether

anything from essay to e-mail — with a couple people looking over their

shoulders. I’m no exception, and Don Hall is almost always there. (And I

suspect as I get more prolix with age, he gets unhappier with me.) (And he

doesn’t like all these parentheses either).

Mostly,

my admiration for his work begins in the voice, hence my pleasure at

hearing/reading that voice again. I can yoke “hearing” and “reading” because

some of the same qualities come through both. These are undefinable, but

unmistakable, qualities that define the essence of the man. They emerge from

the round tones of the podium — as he likes to say, “We rise to assonance.”

They riff off the ground rhythm of the language — he once told me that he and

Donald Justice would carry on conversations in iambs. They grow directly from

his tone — the Harvard bite of clever, the sly New Hampshire wit, the genuine

and naked laugh.

But I

should get out of the way and let the words speak for themselves. Here’s a

paragraph that talks about the lost muse.

“Poems are image-bursts from

brain-depths, words flavored by buttery long vowels. As I grew older — collapsing

into my seventies, glimpsing ahead the cliffs of the eighties, colliding into

eighty-five — poetry abandoned me. How could I complain after seventy years of

diphthongs? The sound of poems is sensual, even sexual. The shadow mind pours

out metaphors — at first poets may not understand what they say — that lead to emotional

revelation. For a male poet, imagination and tongue-sweetness require a blast of

hormones. When testosterone diminishes . . .” [Hall’s ellipsis]

I read

this paragraph slowly and carefully, and I think it’s maybe only the line break,

not the poetry, that has abandoned him. But the metaphors don’t “pour out”

anymore; now he writes what he sees, and he tells stories. And if you’re 86 and

still writing, the truth is never far away.

“Old age

sits in a chair, writing a little and diminishing. Exhaustion limits energy.

Yesterday my first nap was at nine-thirty a.m., but when I awoke I wrote again.”

“[A]mbition

no longer has plans for the future—except these essays. My goal in life is

making it to the bathroom. In the past I was often advised to live in the

moment. Now what else can I do?”

“In the

morning [my companion] stirs quantities of sweet onion and five-year-old

cheddar into a four-egg omelet, which is outstanding. She leaves to teach

French 4. I pick up my pen.”

Pick it

up, again.

But then

the guy watching over my shoulder tells me, “Essays, like poems and stories and

novels, marry heaven and hell . . . . [I]f the essay doesn’t include

contraries, however small they may be, the essay fails.” Okay.

At

eighty, Hall surrendered his license after two minor accidents, giving up what

was left of his physical independence. Soon after, he dreamed he was in a

frightening house, wanting to escape, searching for a door he couldn’t find. He

was in a house without doors. Then, in real life, he unwittingly left a

cigarette ember in his blue chair. During the night, he was startled awake by a

smoke alarm and saw smoke pouring into his bedroom through the door. The Life Alert

he wore around his neck saved him.

Imagine

a smoldering and shredded blue chair standing alone in the snow, a chair that

hosted decades of writing. Or just imagine being 86 years old. Is that contrary

enough?

********

All quotations are from Donald Hall, Essays After Eighty (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014).

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

What Are People For?

“And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be

fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have

dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every

living thing that moveth upon the earth.” Genesis 1:28

“Monks, we who look at the whole and not just the

part, know that we too are systems of interdependence, of feelings,

perceptions, thoughts, and consciousness all interconnected. Investigating in

this way, we come to realize that there is no me or mine in any one part, just

as a sound does not belong to any one part of the lute.” Samyutta Nikaya, from Buddha Speaks

This is a

moral tale about me and an infection: giardiasis, beaver fever. Giardia

lamblia trophozoites live in the small intestine of the host—in this case,

me on my third straight day of a hosting that was ruining a visit with my

sister in Hampton, Virginia.

A

trophozoite is a parasitic protozoan. Giardia lamblia is slightly elongated

with two nuclei, cartoon-faced, victim of caricature. When the Giardia

protozoa attach themselves in numbers to the small intestine, they promote what

any kind of intestinal irritation promotes—but on a scale that seems, at the

time, epic. I think I carried my

protozoa to Virginia from a spring pool in the Adirondack State Park.

Not to put

too fine a point on it, but giardiasis leaves a lot of time for sitting around

and contemplating, generally about giardiasis. Questions arise: what are humans

for anyway? The answers are humbling.

On that

third day of my sitting in, the air temperature had reached 100 degrees, with the

heat index over 115. The local paper

explained that the heat index measures apparent temperatures, the combined

effects of air temperature and humidity.

At 115 we were to watch out for likely sunstroke, heat cramps, and heat

exhaustion—and for possible heat stroke.

The same

paper sent a guy around to take the temperature of various points of human-sun

contact: a parking lot surface was 118,

beach sand 120, and leather car seats 131.

A Slurpee was 23 degrees.

This helped

a lot. We seem to enjoy trying to

express natural phenomena as they relate to humans in numbers—the Enhanced Fujita

Scale for tornadoes, the Saffir-Simpson Scale for hurricanes. But the newspaper story went even further, translating

numbers into observable truths as well. I itched to try it for myself, and a

day later when G. lamblia took a

break I did a dumb thing.

~

My sister

and her husband live in a stunning house with an even more stunning view. Looking east from their second floor balcony

you first see White Marsh, a wetland area whose edges are made up mostly of

groundsel trees, phragmites, miscellaneous scrub, and some young loblolly

pines. Only an occasional storm tide

washes this area. Through this high

marsh runs a tidal creek called Long Creek, with its accompanying mud flats and

spartina grass. Then farther east is

White Marsh Beach, a sparsely wooded barrier beach. Then the Chesapeake Bay. But from the first floor, the view of the

flats was being obscured. The vegetation

in the drier part of the marsh, normally about six feet high, was slowly

returning to woods. More and taller trees were growing in, especially one loblolly

pine that stood about 100 yards into the marsh: my goal. I got permission, gathered

loppers, pruning shears, and a buck saw. I bundled up in gloves, jeans, and an

old shirt. Having decided that alternating

between 100-degree natural air and air conditioning at half-hour intervals

would satisfy those in the media who said not to go outside no matter what, I

began to cut a trail. My work, it turned out, became a drama in three acts.

~

Act one was

mostly expository. I learned about smilax rotundifolia, commonly known as

greenbrier, a member of the lily family that made me rethink all those precious

lily images. My field guide mentioned

heart-shaped leaves, stout thorns, and putrid-smelling flowers. The flowers smell bad in order to attract

carrion flies, greenbrier’s chief pollinators.

Whether carrion flies or some other appalling flies, I learned of flies

too. Usually they land on you, begin to

bite, and you flick them away. But in a

marsh dominated by “stout thorns,” one more sting goes unnoticed—until it

intensifies to a point at which you look down and see a black, triangular fly

attached to a spreading blood stain. And

you’ll wonder what species of road kill your

fly laid her eggs on that morning.

I also

learned that shedding blood is not an exigency in White Marsh; it’s a way of

life. This is because the other dominant

plant beside greenbrier is from the rose family, genus rubus. These are brambles—no

need to get more specific. They, as

everyone knows, have stalks that hurt like hell if you touch them and that

eventually bend over to take root a second time, forming a grounded arch of

pain waiting to slash at your shins, arms, or face. In White Marsh, greenbrier

vines wind themselves around brambles and then tie the prickly bundles to groundsel

trees and phragmites. I had to cut my

path one tendril at a time.

So I did

that because I was too stubborn to quit and because it really wasn’t all that

bad. My clothes were soaked through with

sweat; blood was everywhere, bright red and fresh then drying black in the sun. But I knew I was safe from heat stroke; air

conditioning was only a few minutes away.

And then there were all those millions of parasitic protozoa depending

on me for their existence. The truth

here, as often happens, was relative.

Compared to giardiasis, this was downright festive.

Toward the

end of act one, I began to notice bird sounds: crows and gulls over Long Creek

and purple martins feeding overhead. I

worked on, paying them little notice except to wonder if birds sweat. And then I remembered that, stretching the

term “sweat,” they do—in the sense that they cool themselves by increasing

their respiratory rate and, thereby, the amount of moisture evaporated from

their respiratory tracts. It’s called

thermal polypnea. I recalled seeing

robins sitting with their mouths open, panting, which is what I went inside and

did as well.

~

I changed

my shirt, drank a couple bottles of water, watched the Weather Channel briefly

(air temperature—90, heat index—119), then began the second act, which turned

out to be more introspective. I had

settled into my environment and my work.

I found that by moving slowly I could keep my panting to a minimum and

also reduce the number of the worst and deepest cuts. Two episodes penetrated my mindless haze and

brought me back to my true purpose.

First, I

came upon a deer trail. One minute I was

hacking through a green and brown tangle that limited my visibility to a couple

feet, and then I was looking down a clear path of easy, graceful curves that

led eastward at least thirty feet before it disappeared. My first thought was that my job had suddenly

become easier. Then I thought about the

poet Gary Snyder because I think of him whenever I see deer trails. In his poem “Long Hair,” he writes about a

world taken over by deer: deer trails

everywhere, deer everywhere. I said the

last line out loud: “Deer bound through

my hair,” and I enjoyed the image as I pruned away the few briers that the deer

had stooped under. But the feeling faded. Snyder’s peaceable kingdom of hair and

grasses and deer and men wasn’t working in the face of all that truth about

intestinal parasites and heat indexes and pricker-bushes. My presence was an intrusion, and a contrived

one at that. If I had come upon a deer

sleeping the day away under the cover of phragmites, it would have snorted and

crashed away to safety. I would have

yelped and tried not to fall over backward.

The truth was that the deer path was a poem, and when it veered suddenly

to the north, I had to leave it to cut my way into the brush again.

I had

penetrated five feet or so when I spotted something white another five feet

away. As I hacked closer, it became a

wonderful flower; then a single blossom, trumpet-shaped and the size of my fist;

then white petals with a hint of yellow, brilliant yellow stamens, and all set

against a background of stippled sunlight and leaves of the deepest green. I stood, covered with bugs and blood and

itches and laughed at such a beautiful thing.

And the purple martins called overhead, insects hummed, and deer

slept. It was time to go inside again.

I checked

the Weather Channel (holding at 98 and 119) and my field guide. The flower was jimsonweed, named for the

nearby, early-Virginia colony of Jamestown. It is a totally poisonous plant: touching the leaves and flowers can cause

dermatitis; cattle and sheep are killed when they graze on it; children have

died after eating the fruit.

~

Act three,

the reversal and denouement, were without incident. I came first upon a small grove of

loblollies: ten of them, ten feet high and about two inches in diameter. They were spindly things, bare trunk to about

five feet where the branches and long, graceful needles appeared. With the buck saw, I flattened the grove

easily and made a brush pile for winter storm tides to pull eventually into

Long Creek.

I reached

my target tree in another fifteen minutes.

It was fourteen feet tall and six inches in diameter. Sawing this one was harder work. Bending over made me woozy, and the

undergrowth made it almost impossible to keep the buck saw from binding. So I

decided to cut it at four feet then take the stump separately. Without remorse, I felled the pine and

counted the rings—twelve years. Bending

to finish the job, I felt the first chills of heat exhaustion. My stomach flipped around a bit like the

start of seasickness. I quickly turned

my back to the marsh. A/C, cold shower, curtain.

~

It had been

a good day. I had learned a little about

how I fit in—to White Marsh, Hampton, Virginia, North America, Earth. G. lamblia feasts off my gut; I’m compelled

to chop down whatever symbolic tree gets in my symbolic way: how are those two

different? Powerless to resist, I had naively

tried to re-establish my dominion. But my good day turned into a long

night. Those Giardia parasites, as they

tend to do, had called in reinforcements, and I was awake yet again. A hint of earliest light over the Atlantic

drew me first to the sliding doors, then to the dark outside. The sounds of cicadas and other night bugs

gnawed away at thick and sticky air. In

the marsh, clapper rails yapped at each other like neighborhood dogs. And far away the surf pulled at White Marsh

Beach. I was imagining the hiding places

of rails and thinking about deer making new paths through the marsh when the

itching started from the first no-see-um bite.

No-see-ums. Midges. Genus culicoides. Nearly invisible, the females break the skin

with small cutting teeth and, at the same time, inject a chemical from their

saliva that prevents clotting. Then,

without remorse, they suck up the tiny pools of blood.

********

The image of Giardia lamblia is from paleovegan.blogspot.com

Portions of this piece were published in Ascent

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

Stumbly, but Not Half-Assed

Writing

is my livelihood, I dabble in bonsai, and I recognize a strong kinship between

those two things. But the whole vocation v. avocation, work v. dabble, duality

doesn't quite convey the way I think about it. I'll circle back.

~

I've

noticed some confusion in the gradual and natural winnowing effect of

experiences over the decades; to extend the image, what was apparently wheat

has turned to chaff or often the other way around. For example, a long time ago

I watched my friend Bill, who had been my only real male friend growing up,

play the role of Jerry in Edward Albee's Zoo

Story. Thinking back on the experience, three impressions return.

Remember

the play? Jerry confronts Peter in Central Park and imposes an increasingly

disjointed conversation on him that culminates in Jerry's telling THE STORY OF

JERRY AND THE DOG!, the ongoing struggle between Jerry and his landlady's

mongrel. Things get less rational, more physical; Jerry forces a fight and

impales himself on a knife Peter is holding. So the first impact on me was the

distress of watching your best friend from your high school days turn into a

crazy guy in front of you. In public.

Then,

with a little distance, I remember Zoo

Story's familiar themes. The play is about all those mid-twentieth-century

concerns that have faded from favor over the years: the distance between

people, the triumph of materialism, the absurd arbitrariness of experience.

I can

conjure these when I remember watching the play back then. But what came to

mind just recently — spontaneously — was the phrase Jerry uses to describe the

dog dedicated to tearing him apart. "He was sort of a stumbly dog, but he

wasn't half-assed, either. It was a good, stumbly run, but I always got

away." Stumbly, but not half-assed.

T-shirt, if not actual epitaph material. I guess if one of Albee's themes was

about the dislocation of experience, it took.

The

phrase came to me when I was thinking about a cotoneaster plant I was pruning.

So to be more precise, then, my work with bonsai is stumbly, but not

half-assed. I don't dabble, I commit. And it's not always easy.

~

I feel

the weight of a history that runs from the Tang Dynasty Chinese practice of

what came to be called penjing (or pen ching) through Japanese bonsai and down

the centuries to my workbench. I know about how early penjing specimens were oddly shaped trees thought to have magical

powers. These were followed by re-created landscapes in trays — plantings of

rocks or more complex arrangements of rocks, plants, and decorations — creations

that, if not religious, were at least mysterious enough in their ability to

miniaturize nature to contain their own sort of power. When the practice of

tray planting (pen tsai in Chinese)

emerged in Japan as bonsai, its aesthetic was simplified to correspond to Zen beliefs.

A bonsai composition came to comprise a single tree, and I try to see each tree

as an embodiment of the entire universe.

But I'm

defeated. Often it's simple fear at the moment of pruning a branch — gone

forever, the harmony destroyed. Or it's the cold reality that true bonsai take

many years to become convincing; I might not live to see any project through

to completion. And I'm defeated also by my own confusion. I'm not comfortable

with the control element of bonsai, which seems to appropriate the

Judeo-Christian idea of nature existing in service to humans. In theory, the

practice honors the natural world by trying to understand it, but recreating it

and controlling it using techniques such as wiring, defoliating, and trunk-chopping

feels hubristic.

What I

settle for is the Zen truth from that famous Buddhist aphorism: Better to

travel well than to arrive. At no point are the plants under my control;

they're in charge, and the best I can do is cooperate and sometimes collaborate.

And I can just enjoy the process, stumbly as it is, and what the process

teaches.

~

Since

most dictionaries, if they acknowledge “stumbly” at all, assign a prosaic

definition — "given to stumbling" — I feel free to offer my own: Stumbly adj. 1 something lacking in polish that is produced by an engaged maker;

2

a condition required to produce such a result. To be stumbly is to be

enthused, unguarded, honest. It insists on mindful attention to each moment at

a task. It cares little for "outcomes," avoids the cheap, the

hurried, the vain. And now the topic is shifting here — from bonsai to writing

to a way of living. It turns out that stumbly and "not half-assed"

are the same thing; work and play can be likewise joined by a dedication to

mindful living.

Paul

Valery gets translated repeatedly in workshops and writer interviews as saying

a poem is never finished, just abandoned. I think closer to what he really said

was "A work is never completed except by some accident such as weariness,

satisfaction, the need to deliver, or death." Same thing, just more

specific: the point is that you can choose to be satisfied or you can die; you may be finished but your work isn't.

And note that Valery's list doesn't

include a frantic need to publish as many works as possible that leads

to dashing off a poem in one sitting and submitting it, simultaneously, to two

dozen journals.

Also in Zoo Story, Albee has Jerry observe “sometimes

a person has to go a very long distance out of his way to come back a short

distance correctly.” That may be gibberish, or it may be useful — the two are

sometimes so close together I have trouble telling them apart. In the context

here, though — of bonsai, writing, and editing — Jerry seems to have been given

a moment of clarity. At any time on the way to the zoo, you can’t be anywhere

else except where you are. Might as well give each stumbly moment its due.

*********

I'm

obviously ignoring my own counsel by writing a blog; however, I will take my

own advice and not publish a photograph of my own bonsai. The one that precedes

this piece was taken in the North Carolina Arboretum's bonsai exhibition garden

in Asheville, North Carolina.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)